Can physicians and nurses provide quality care through a computer connection? (AARP)

Mercy Virtual has been called a hospital without patients, and the description is both true and false. There are neither beds nor patients in the gleaming four-story medical facility, which opened in late 2015 in Chesterfield, Missouri, a St. Louis suburb. But the facility is a hub of very real care for very real patients, in hospital beds and at home.

Part of the Mercy health care system, which spans 44 hospitals in the Midwest, Mercy Virtual is the incarnation in bricks and mortar of what has generally been consigned to the ether: virtual care.

Also referred to as telemedicine or telehealth, virtual care involves the remote diagnosis and treatment of patients by medical experts who are miles or even continents away. Heralded as a way to save money while providing quality care for patients who might not otherwise have access to specialists, telemedicine has exploded in growth during the past decade. One report claims that, globally, telemedicine will be a $36.2 billion industry by 2020, up from $14.3 billion in 2014. This new approach to health care is of particular importance to older Americans, because it creates the potential of putting a virtual doctor or nurse right into the homes of patients, as frequently as needed, monitoring their health and making real-time diagnoses and treatment adjustments.

While many health care providers are developing elaborate virtual-care operations, no other single initiative to date reaches the grand scale exemplified by Mercy Virtual, the first built-from-scratch virtual-care center in America. With a team of more than 700 physicians, nurses and support staff serving 750,000-plus patients last year, Mercy Virtual is an experiment in telemedicine writ large.

But does it work?

Read More: True Nature (TNTY) Readies Launch of Mitesco: “The Medtech Incubator”

Gauging virtual care

Let me introduce myself: I am an academic physician specialized in internal medicine and preventive medicine, and the founding director of Yale University’s Prevention Research Center at Griffin Hospital. Until I turned my attention to Mercy, I was relatively uninitiated in the ways of virtual health care. In truth, my predispositions were mostly negative, and my skepticism ran deep. Wouldn’t bedside and virtual care conflict? Wouldn’t there often be added cost, without added benefit? Wouldn’t the technology prove daunting for homebound patients? Most important, wouldn’t virtual care be impersonal, without the human touch that so many of us see as central to the healer-patient relationship?

Mercy was eager to address my questions and hosted me for two full days, to observe its processes and meet with staff and patients. Federal privacy laws prohibited me from talking with random patients or viewing any case details; the patients I spoke with were cleared in advance by Mercy. That said, my access to staff, patients, facilities and information seemed more than sufficient for me to make a reliable assessment.

Seen from the outside, Mercy Virtual is a sleek and inviting place, the mostly glass facade offering glimpses of warm wood and large spaces. Inside, a wide central staircase and open layout are conducive to impromptu group conversations. At the same time, clever engineering allows for privacy protection in the patient-care areas; partitions on swivels look like a hybrid of giant wings, umbrellas and hot-air balloons. The effect would be more mystical than medical were it not for the state-of-the-art consoles and mass of neatly arrayed clinical information on multiple computer screens at the heart of each hub.

JEFF WILLSON

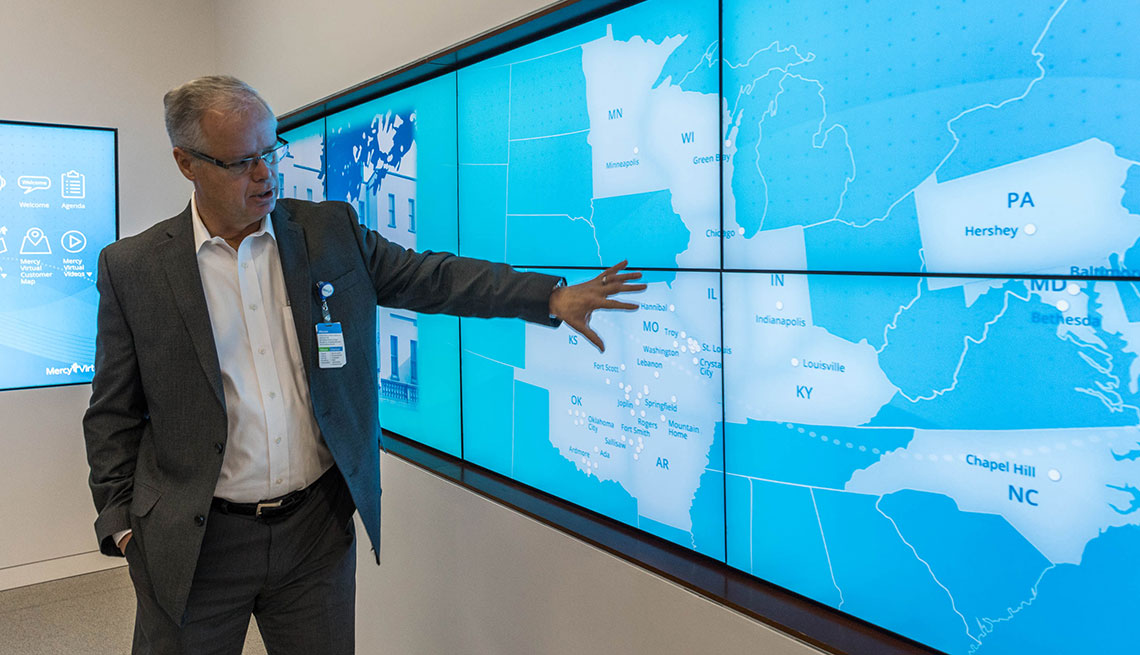

Randall Moore, president of Mercy Virtual, shows the hospital locations served from the Missouri facility.

Inside every hub, nurses and physicians monitor computers that detail vital statistics for distant patients across multiple hospital locations. The same readings at the nurses’ station down the hall from a patient show up on Mercy Virtual’s computer screens, giving the experts a full view into a patient’s status. But the virtual model goes far beyond the usual patient-vitals review in scope. Among other things, it uses artificial intelligence to filter and flag medical information, automatically moving the patient with the most serious condition, or whose condition is deteriorating, to the top of the roster — a sort of automated triage not typically available to a doctor running rounds in a standard hospital. Another benefit: The virtual-care center is immune to the “alarm fatigue” — the exhaustion caused by seemingly never-ending tasks and crises — that plagues care providers in busy intensive care units.

Mercy Virtual runs 24 hours a day, like any other hospital. But because it is providing virtual “backup” for other hospitals, its services are needed most at night, when staffing at the remote bedside is thinnest. From a distance, the clinicians do many of the tasks that bedside physicians would do, such as monitor health readings, respond to alarms, answer nurses’ questions and make medication decisions.

At 8 a.m. the center was quiet, even peaceful. My escort, Randall Moore, M.D., president of Mercy Virtual, personifies this place. Imposing, with an air of natural authority carried on a 6-foot-3-inch frame, he quickly convinced me he is the very thing health care needs more of: someone who cares about the patient before all else and applies creative intelligence to enhance the care he or she receives.

An internist by training, Moore was working in the intensive care unit at Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore many years ago when he first noticed that software could detect abnormal patient readings not picked up by clinicians until hours later and that those hours could make huge differences in outcomes. This widely accepted insight is at the heart of all care delivered through the world’s first fully virtual hospital — that by detecting problems early among patients, Mercy will realize big savings and provide better care.

“If we can start with the sickest patients and have the biggest impact financially, we can use that cash flow and move all the way back to primary prevention,” Moore says.

JEFF WILSON

Bob Garbs, 83, participates in Mercy Virtual’s Engagement@Home program.

The Patient’s Point of View

Bob Garbs, 83, participates in Mercy Virtual’s Engagement@Home program, in which patients get care at home or another location besides a hospital. I looked on, with his permission, while a “care navigator,” Emily Roper, a young woman just out of college and trained by Mercy Virtual, talked to Bob and a great-nephew who was visiting. Bob’s smile on the computer screen brightened the room, and the conversation with Roper was so warm and friendly that I got the vague impression he might be trying to set up his care navigator with his great-nephew.

When it was time to review Bob’s clinical status, the video connection was passed to nurse Lori Tasche. While obviously focused on Bob’s health status, this part of the “visit” also looked and sounded like an interaction between people who knew each other well and cared about each other a lot. Looking for the impersonal liabilities of care across miles, I saw no real evidence of it from the delivery side.

The next day, I sat with Bob in his home, 40 miles from Mercy Virtual, in Washington, Missouri. For Bob, these daily visits as part of Mercy’s Engagement@Home program have been nothing less than a life changer. A former smoker with advanced pulmonary disease, he had been struggling to get enough breath just to make it through another day when he first entered the program. Now, set up at home with an iPad video camera and a nebulizer, and with continuous monitoring and virtual encounters at whatever frequency is warranted, he reports that every day is better than the one before. “I don’t think I’d be here anymore if it weren’t for the virtual-care program,” Bob told me. “I call them my Mercy angels.”

His wife, once constrained by her husband’s condition, now has what Bob notes is one of the program’s many benefits: peace of mind. When we visited, she was out shopping — because she could.

Much the same story played out at either side of the other virtual-care situations I encountered. I first met Gloria Gill, 72, via a video screen, about 40 miles from where she lay in a hospital bed in Mercy Hospital Washington’s intensive care unit, also in Washington, Missouri. Gloria had far more clinical details to discuss because she was acutely ill, but aside from that, her interactions with the care team at Mercy Virtual were nearly a replay of Bob’s: warm and intimate.

The next day, I visited Gloria at her bedside and, as with Bob, saw the video conversation from the other side. The video camera was fixed to the wall of the hospital room and could pick up and transmit very high-resolution images of Gloria, who, in turn, saw her care team projected right onto her television. Of course, all this discourse was subject to the federal government’s stringent health information privacy rules; when not serving as a video connection, that camera in Gloria’s hospital room was angled against the wall to show it was inactive.

Gloria was receiving treatment for pneumonia that had come on several days earlier, heralded by severe chest pain. Naturally chatty and, I think, enjoying all the attention, she talked about the many advantages of virtual care in the hospital. But Gloria was in the virtual Engagement@Home program, too, and spoke as much about that.

“There’s always somebody, and they’re just a call away—it gives me such peace of mind,” she told me.

Enrollment in Engagement@Home in no way displaces a primary care provider; it’s an add-on, and one often recommended by the primary care doctor in the first place. As soon as her pneumonia symptoms emerged, Gloria used her iPad to contact the virtual-care team at Mercy, and they took care of the rest, arranging for her transfer to the hospital, alerting her primary care provider and overseeing her initial treatment.

Contrast that to hours spent at home wondering what to do, followed by hours in a crowded emergency room before anyone looks in on you, and you start to see the powerful benefits of virtual care.

“There’s always somebody, and they’re just a call away — it gives me such peace of mind.”— Gloria Gill, Mercy Virtual patient

Are We in the Way?

Gavin Helton, M.D., the gentle, caring medical director of Mercy Virtual and the center’s Engagement@Home program, told me he loved the primary care practice he had built up over 17 years. So it was a bit surprising to find him a video monitor away from those patients now. He explained that he did, indeed, need to be cajoled into his current position by Mercy Virtual and accepted it only with assurances that he could return to his practice if he missed the joys and intimacies of direct patient care.

To smooth the transition for himself as well as his patients, Helton at first made routine trips to the homes of new participants in the virtual program—to help get them set up and to understand the “feel” of Engagement@Home on their side of it. Two years into the program, he tells me he is finding virtual care as fulfilling as his previous practice. Plus, he has the means to reach many more people and make a much greater contribution this way. “I feel like half the state of Missouri has my cellphone,” he jokes.

With nothing but rosy reports from both sides of the virtual encounters, I thought there might yet be gripes among doctors who felt that they were being crowded out by a virtual overseer. If anyone was going to tell me why the practice had drawbacks, it would be William Galli, M.D., or nurse Miranda Pickens. When I visited the ICU at Mercy Hospital Washington, Galli was the presiding intensive care specialist, and Pickens was one of the staff nurses. Surely, I thought, one of them would have misgivings about all that surveillance.

Not so. Galli, as open and friendly with me as he was methodically efficient when it came time to run ICU rounds, had only praise for the virtual-care program. He told me his autonomy was in no way compromised, yet he could sleep better at night knowing that a virtual-care team, including a certified intensive care specialist, was monitoring the patients continuously. Pickens agreed and noted how much the nurses appreciated nearly instantaneous access to an expert physician whenever needed.

“We resuscitated a patient at night with the tele-ICU physician in charge via video, and the patient had a phenomenal recovery,” she said. “Pressing a button and getting the doctor in less than a minute — it’s that quick.”

The Diagnosis

Whether other hospital systems can, or want to, replicate Mercy’s specific model is still to be determined. And more data need to be collected and analyzed in areas such as patient-usage patterns and the barriers of entry for health care providers. But Mercy has already shown that as a business model, virtual care can be a winner—that it can reduce health care costs, improve efficiency and lead to improved patient outcomes.

“We resuscitated a patient at night with the tele-ICU physician in charge via video, and the patient had a phenomenal recovery.” — Miranda Pickens, ICU nurse, Mercy Hospital Washington

Overall, I was impressed. From what I witnessed, virtual care was convincingly enhancing the timeliness and quality of health care delivery to patients, without sacrificing the human touch. I was skeptical when I started this assignment; after my days of visiting and weeks of studying, I emerged not only enthusiastic but excited about virtual care’s capabilities.

Plus, it got me to ponder: What’s next? While Mercy operates a vast health network, including many rural facilities, I can envision even greater benefits to applying this virtual-care approach in urban settings, where hospitals are often under greater financial and clinical pressures because of their larger patient populations. Over time, the Mercy system also offers the promise of creating social groups among patients, so no one is left to face a medical challenge alone.

Even more promising, though, is the possibility that Mercy will help speed the needed transformation of a “disease care” system into a system of actual health care, in which doctors focus as much on prevention and healthy living as they do on cures and treatments.

How? By detecting problems early in hospitalized and ambulatory patients alike, Mercy Virtual is reducing hospital admissions, emergency-department visits and extended hospital stays, saving millions of dollars. Mercy plans to invest a portion of that savings into a portfolio of health promotion and disease-prevention programming. That was music to this preventive medicine specialist’s ears. I am tempted to tell you to get in line when virtual care comes to a hospital or clinic near you, but there’s really no need. They’ll come to you—it’s what they do.

David L. Katz, M.D., is the immediate past president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine and founder of the True Health Initiative, a nonprofit that promotes healthy living. His next book is The Truth About Food, due out this fall.